5 Common Misconceptions About Basic Violin, Viola Technique

Share

By Rozanna Weinberger

The following article covers 5 common misconceptions typical among players young and old. More advanced players may also show elements of these issues that were never fully overcome causing technique to be more challenging while technical execution may be less than maximum efficiency.

-

When holding the violin/viola the instrument stays in place by clutching it between shoulder & head. This is certainly one of the most common misconceptions born of another problem when students aren’t taught to differentiate between the shoulder and rib cage. But the truth is, the upper body can be supported by the muscles surrounding the rib cage and supporting the torso by raising shoulders is really overkill. Its not actually the raised shoulder that secures the instrument but the counter direction of the chest in relation to the instrument. Often people will carry emotional stress in the shoulders and this is manifested by hunching or raising the shoulders. In fact it’s possible to ‘hold oneself up without raising the shoulders. If one examines the skeleton, its clear the shoulder girdle does rest on the rib cage. While there are many possible movements the shoulders can make, which include being elevated, its not essential to elevate the shoulders to secure the instrument. The rib cage has the ability to work in opposition to the legs & feet, elevating the upper body and lengthening while legs & feet create a grounded feeling in the body. A feeling of growing taller in the rib cage, neck & head, countering the sense of being grounded with ones feet, is a potential when playing.

-

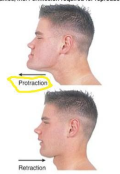

Its necessary to jut out the chin and neck to secure the instrument.

In fact doing so puts the body in an unnatural position that is difficult to sustain without exerting stress and undue tension over time. Try a simple observation to notice what it actually feels like. (Too often in the stress of trying to secure the violin, beginners will ignore the discomfort in the

moment because it may seem like the only option.) Without even trying to hold the violin simply jut the neck & head forward in relation to shoulders then allow them to relax back.

3. The right shoulder is a fulcrum from which bow stroke derives. In fact the shoulder ‘goes along for the ride’. While its true the shoulder does not remain motionless and may elevate and drop, it is like a part of a larger set of physical mechanics and moves in response to other muscles and parts of the skeletal system movements. There are many ways of connecting to the back involvement though getting in touch with the back can feel like an incredibly illusive endeavor at first. The simple ‘Chicken Wing’ movement of placing lright hand on left shoulder then elevating right elbow is a simple way of noticing the muscles at work under the scapula.

4. The right hand position is static and once positioned on the bow, never changes. The idea of balance vs. grabbing the bow is a very important challenge for students to tackle. The bow hand and fingers are constantly reacting to the part of the bow being used and must be able to react. This reaction is what makes real bow control in the same way that a person on a balance beam could never hope to walk a rope by clinging to it with ones toes. This may be more obvious for strokes such as spiccato when fingers more clearly react to the back & forth of the bow. But when playing strokes like detache, legato the hand is constantly responding to the bow. A simple motion study can help one feel the change that occurs from frog to tip. a. Take bow in hand and play short down bow using only 2 inches of bow at the frog. Then hovering over string extend the bow arm to the tip of bow then play an up bow using only 2 inches of the bow then travel back to the frog while hovering the bow above the string. Repeat this a couple times noticing how the hand and arm learn to balance in relation to the bow. The less judgment about the wobbly moments the better one will be able to give the brain the info. it needs to make adjustments on a kinesthetic level.

5. The Index finger deals with most of the weight in the right hand.

Actually if the bow is truly balanced in the right hand, the pinky will feel the lions share of the weight at the frog while the index finger absorbs most of the weight at the tip. A simple study of taking a pencil in ones hand and causing tip to point upwards perpendicular to the floor by straightening pinky demonstrates the balance in the hand. Pointing tip in the opposite direction towards the floor, notice how the index finger leaning against the pencil will allow this to happen. Although the bow is heavier and more challenging to manage because of the weight, this teeter totter type movement can help one understand the components of balance and constant adjustments that the right hand is capable of making to accommodate bow stroke.