Most Common Misconceptions About Posture In Viola/Violin Playing

Share

by Rozanna Weinberger

Have you ever noticed how many string players tend to carry themselves with a

Jascha Heifetz Now that’s posture!

curvature of the spine and sloping shoulders and back, even when not playing the instrument? Its amazing how we can develop physical habits unconsciously. The thing is, you’d never see a dancer develop a slumping posture over time. Sure its in their skill sets to develop a super fit body but its also part of their skill sets to learn how to use the body optimally. When you think about it, why shouldn’t such considerations as optimal body movement be part of a string players skill sets?

Particularly in orchestras, players often carry themselves with shoulders sloped inwards. This is not a criticism but an observation and may in part be an effort to get closer to the music stand or could be a result of fatigue. The subtle workings of the upper body and abdominal muscles are only recently becoming understood when it comes to their impact on optimal string playing. And while its certainly possible to ‘get away’ with sloppy posture with respect to string playing it ultimately comes down to the ability to do difficult things (playing the instrument) easily or with great difficulty. Herein lies the difference between players that are considered naturals vs. everyone else and if they do seem natural chances are they’re moving efficiently to a large degree.

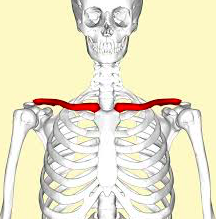

Google photos The clavicle forms a wonderful natural ‘shelf’ for the instrument.

In general, anything that makes it more difficult to counter the effects of gravity, with respect to violin hold, will inevitably lead to gripping the violin between the head & shoulder. While curving and simultaneously jutting forward the shoulders is a typical stance of many string players, a healthy relationship to the instrument requires the exact opposite impulse. Otherwise the instrument will want to fall because of the angle created while slumping the shoulders forward. The tendency to jut the shoulders forward is a way of compensating for a sense of insecurity in holding the violin. On the other hand, if the upper toros is sufficiently supported by the abdominal muscles then the upper body can also effectively counter the weight of the violin and head in supporting the instrument. Turns out, all those illusive muscles we have trained in Pilates, and the like, really did have a use in daily life besides helping us have a better shape. When the shoulders are free to rest atop the rib cage, they can also support and counter the weight of the instrument and head, in a more efficient manner.

While it seems that many virtuosi tend to hold their instrument up high in reality this is a more effective way to counter the effects of gravity, so long as the overall posture is not slumping. This makes possible the use of the clavicle as a perfect natural ‘shelf’ for the violin. But if the upper body is slumping, if the torso is not sufficiently supported by the right muscles, the upper body and will instead be curved forward, making it easy for the instrument to fall to the ground, thanks to gravity.

Most players struggle with keeping their shoulders ‘relaxed’ and the propensity for the shoulder to be elevated stiffly to support the viola/violin and the impulse to tense the shoulder upward in bow arm technique are born of the same fundamental misunderstanding.

Most string players use the shoulders to replace activities that should be happening in other parts of the torso. The notion that we ‘hold ourselves up’ by elevating the shoulders could be replaced with utilizing those muscles we’re encouraged to use in Pilates.

Enter a caption Courtesy of link provided.

A simple motion study of sitting in an arm chair, or any chair that enables one to press the hands against either the arm rests or seat itself. While in seated position, start by pressing the palms of your hands against the arm rest to get out of the chair and notice how the torso responds, elevating itself upwards as the h ands press down and push off against the arm rests. Those illusive muscles that enable us to elevate the torso should also be engaged when playing the viola or violin. If these muscles are doing their job, the shoulders will not be as likely to replace this support. Further, the improved posture will support a body angle less likely to cause instrument to fall.

ands press down and push off against the arm rests. Those illusive muscles that enable us to elevate the torso should also be engaged when playing the viola or violin. If these muscles are doing their job, the shoulders will not be as likely to replace this support. Further, the improved posture will support a body angle less likely to cause instrument to fall.

What does it look and feel like to balance the instrument vs. gripping with shoulder and head? Learning this process can feel like a vulnerable state. And it really does take time, patience and observation. And lest the player confuse the use of a high shoulder rest with a balanced and genuinely secure position, unless the player masters the ability to respond to the ever changing balancing act of holding their instrument, similar to an aerial artist on a tightrope, the player will have to deal with shoulders that are not sufficiently unencumbered. Because when our shoulders and head aren’t engaged in gripping the instruments, we are left to discover the extent to which we seem to have little or no control over the instrument. But that is also the point where balance can be happen and self discovery begins.